“Take your Seat” Law Commission Second Consultation Paper, Issue 1: The Law Commission backs the seat of arbitration as applicable arbitration agreement law.”

This note is the first of three considering the important Arbitration Act 1996 issues being reviewed by the Law Commission in its Second Consultation Paper (see Initial summary). Issue 1 concerns how to determine the law of an arbitration agreement if it is not expressly identified. What does that mean?

1 Separability at a glance

The jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal rests on the deceptively simple-sounding principle of “separability”. Separability is a very useful legal fiction. It has us treat the contractual provisions which record parties’ agreement to arbitrate as a separate agreement from any commercial contract they are contained in. Separability is thus what allows a tribunal to hold that a commercial contract is void or illegal without terminating its own jurisdiction and vanishing in a puff of logic.

2 Separability issues

The undoubtedly useful view that an arbitration clause is a separate binding agreement has complex and controversial implications. It creates two significant, connected issues:

- First, because the magic of separability makes the arbitration agreement a separate contract, if the parties have failed to expressly state what this is, courts have to decide how to determine it. This a task that has proved difficult and has yielded contrasting answers.

- Second, because this separate contract governs all arbitration matters, the express or determined choice of law will have important implications for the parties. These include the following issues (which are certainly not a comprehensive list):

- Whether the non-excludable rules and principles which exist in the arbitration law of a state (known as the lex arbitri) are imported. These can range from the anodyne to the strange, to provisions which would actually invalidate the arbitration.

- The circumstances in which non-signatories to an agreement (like guarantors, parent companies and directors) can be compelled to or opt to join the arbitration as parties.

- What procedural and evidential principles that will govern the arbitration.

- What matters are deemed capable of resolution in arbitration rather than court (a principle known as “arbitrability”).

- Interpreting the scope of the issues that the parties intended to submit to arbitration.

- The applicable confidentiality rules surrounding the arbitration.

- What rights of support the parties will have from national courts (and which courts those will be). This will cover critical issues, often involving third parties, like injunctive relief, disclosure and applications to remove or appoint arbitrators.

- What rights parties will have to challenge an arbitral award in national courts and the time they have to do this.

So – as we can see – there is more to an arbitration clause than might be assumed, and parties ignore arbitration choice of law at their peril.

3 The seat v contract debate: Enka v Chubb backs the “law of the contract” (mostly)

In England and Wales, like in many other jurisdictions, there has been hot debate between proponents of two approaches to determining the law of an arbitration agreement where it is not expressly identified. The two broad camps are (i) those who say that the law of the matrix contract should also apply to the arbitration agreement (because this accords best with the parties’ presumed intentions) and (ii) others who say that what matters most is where the parties chose an arbitration to be seated. Both the “law of the contract” and “law of the seat” positions strain to infer a general party intention. Neither position is totally satisfactory. The questions we can ask about party intention do not have credible general answers: “Do parties really understand separability and its implications?”, “Do parties expect to adopt the laws of a state when they agree to seat an arbitration there?”, “Do parties expect the law of a contract to apply to an arbitration clause if they do appreciate there is a distinct agreement?”

The Supreme Court in its 2020 decision in Enka v Chubb came down strongly in favour of the law of the contract but with some significant equivocation.1 This was confirmed in its further decision in Kabab-Ji.2 The Supreme Court held that (assuming there was no express choice of law concerning the arbitration agreement), if there was a choice of law governing the main contract, this would in most cases apply to the arbitration agreement as well.3 However the Supreme Court made room for the possibility that this general rule “may” be displaced in certain circumstances:

- Where the national law of the country where an arbitration is seated provides that the law of the seat governs (i.e., a modest “power grab” by the seat nation is presumed to be accepted by the parties/is to be respected).4

- If there is a serious risk that the law of the contract would invalidate the arbitration agreement or part of it (an issue noted above). This is known as the “validation principle”.5

- If the chosen seat was England and Wales and there were additional references to a local association or practice (e.g., arbitration in London before the LCIA).6

Interestingly, the Supreme Court disagreed on the approach if there was no choice of law in the main contract (a relatively unusual situation which in fact applied in Enka v Chubb). While it was accepted that it was necessary to apply general conflict of law principles consider what law had the “closest and most real connection”, the majority considered the law of the seat was the most important factor, while the minority considered the law most closely connected to the terms of the contract was more relevant.7

Accordingly, while Enka v Chubb tilted the proverbial table in favour of the law of the contract generally, it contains reservations and does not give a clear answer in all cases.

4 The Law Commission’s proposal – a return of the “law of the seat”

The Law Commission considers that the position reached by Enka v Chubb is complex and creates issues. Considering the above summary, it is hard to disagree.

The Commission proposes that Parliament enacts an amendment to the Arbitration Act providing that, unless there is an express agreement of the law of the arbitration agreement itself (not the main contract), the law of the seat is to apply. The proposal applies whether the arbitration is seated in England and Wales or elsewhere and would effectively overrule the Supreme Court.

As the Commission paper notes there are significant upsides to this position including the following:

- The Enka v Chubb analysis is complex and multi-layered. Depending on the case, proceedings required to establish a disputed choice of law could prove very costly and time-consuming. The approach also makes it difficult for practitioners to advise their clients with a sufficient level of certainty.

- Many international contracts seated in England and Wales are governed by foreign laws. The decision in Enka v Chubb, if not reversed by legislation, stands to make foreign contract arbitrations seated in England and Wales more costly and time consuming since complex expert evidence may often be required to analyse how the foreign law applies to the arbitration agreement and interfaces with English arbitration legislation.

- The principle of separability is arguably not mandatory in the Arbitration Act 1996 and could be disapplied by a foreign law arbitration agreement.

- English law takes a strong pro-arbitration approach to determining the scope and arbitrability of issues. Application of more restrictive foreign law might require that matters which the parties intended to arbitrate be pursued in court.

5 Assessment and tomorrow’s problems

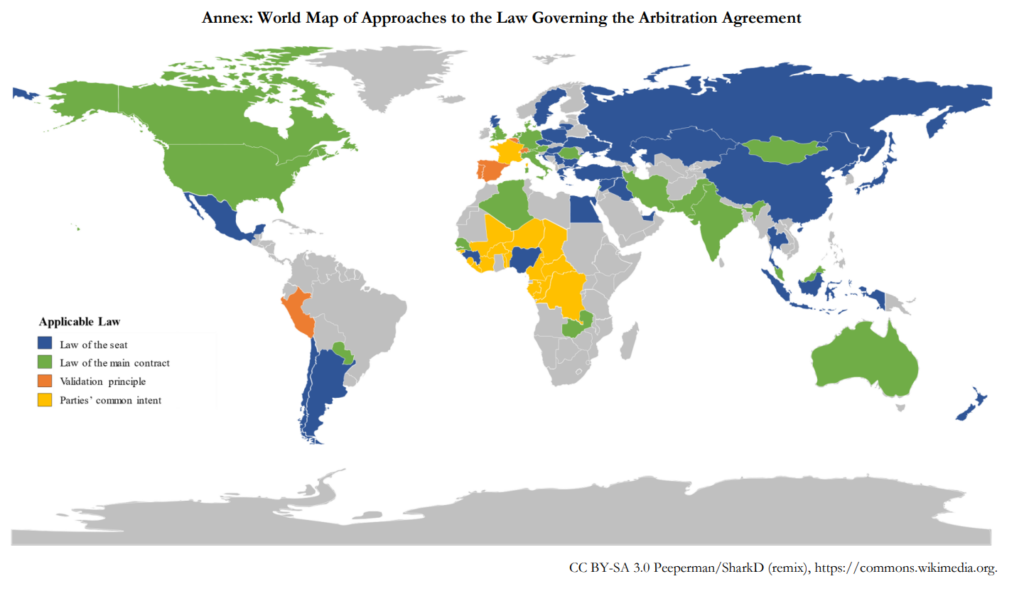

In our view the Law Commission’s proposal is a welcome step in the direction of certainty and clarity in an area where no one approach is correct as a matter of first principles. For such a fundamental issue there is an impressive lack of global consensus concerning approaches, as this map indicates:

If enacted, the proposed reform would re-align England and Wales law with countries adopting different approaches as follows:

- It would be more closely aligned with those which favour the law of the seat approach (coloured in blue), this includes Scotland, Sweden, Turkey, Argentina and Hong Kong.

- It would also be more closely aligned with countries which adopt a “common intention” approach (coloured in yellow), which also favours the law of the seat. This would mean much greater alignment with the French Courts which have famously come to opposing conclusions about the recognition and enforceability of awards.8 For example, in Kebab-Ji, the UK Supreme Court applied the law of the main contract (English law) and determined that there was no arbitral jurisdiction over contract non-signatories. France’s apex court applied the law of the seat (French law), which more readily joins non-signatories and found they were valid parties. The English courts then refused enforcement of the award in England. Having opposing approaches with a major arbitral seat and trading partner is not desirable.

- Because of the flexible approach of countries which adopt the Validation Principle (coloured in Orange, and see above at footnote 4) including Switzerland, Belgium and Spain, significant harmony in the recognition and enforcement of awards should be maintained.

- There would of course be reduced alignment between England and Wales and countries in the club it would be leaving (coloured in Green), including the United States, Australia, India, Germany and Singapore.

What issues would the change be likely to create? There are two particularly significant issues we expect will become more common:

First, because, as the Law Commission noted, parties regularly opt to seat arbitration in London in foreign law contracts, there will be more arbitrations where the arbitral law is (on the Commission’s approach) different from the law of the contract. This may create difficult issues in cases about the scope of matters which are covered by the arbitration clause and the substantive contract (and the categorisation of legal issues as “procedural” or “substantive”).

Second, it is possible that countries which apply the law of the contract approach may refuse to recognise and enforce awards in international arbitrations on the grounds of “public policy” under Article V of the New York Convention. In other words, the France-England scenario could now play out between England and New York. This risk is probably less pronounced, however, because the law of the contract countries are mostly common law legal systems. Their laws on arbitration agreement issues (such as joining non-parties) are generally closely aligned, minimising public policy issues.

In short, the Law Commission has proposed a new approach which is simpler to understand and likely to minimise problems in a difficult area. This is the gold standard of legal reform.

If you have any questions about the Arbitration Act reform or any other arbitration issues, please feel free to contact Rob Schultz.

________________________________________________________

[1] Enka Insaat ve Sanayi AS v OOO Insurance Company Chubb [2020] UKSC 38, [2020] 1 WLR 4117.

[2] Kabab-Ji SAL v Kout Food Group [2021] UKSC 48

[3] At [170(4)], [257(3)] and [266]-[267].

[4] At [29].

[5] At [69]-[71]. In relation to the validity of arbitration agreements, some countries take a generous approach to the validation principle and provide that an arbitration agreement will be valid it is valid under any one of the potentially applicable laws. This is essentially a middle ground between “law of the seat” and “law of the agreement”.

[6] At [114] and [257(4)]

[7] At [170(8)], [257(1) and (2)], [282] to [283] and [286].

[8] Cour de Cassation decision no 20-20.260 of 28 September 2022 – the French decision in Kabab-Ji.